Casablanca – Morocco has decided to extend the suspension of its soft wheat import subsidies through the end of 2025, maintaining a strategy that capitalizes on favorable international market conditions while addressing ongoing domestic agricultural challenges.

The National Interprofessional Office of Cereals and Legumes (ONICL) confirmed that the state’s compensation mechanism for wheat imports will remain inactive for July, continuing a trend that began earlier this year. This policy decision reflects both the stability of global soft wheat prices and the government’s intent to reduce unnecessary public spending.

Global prices below subsidy threshold

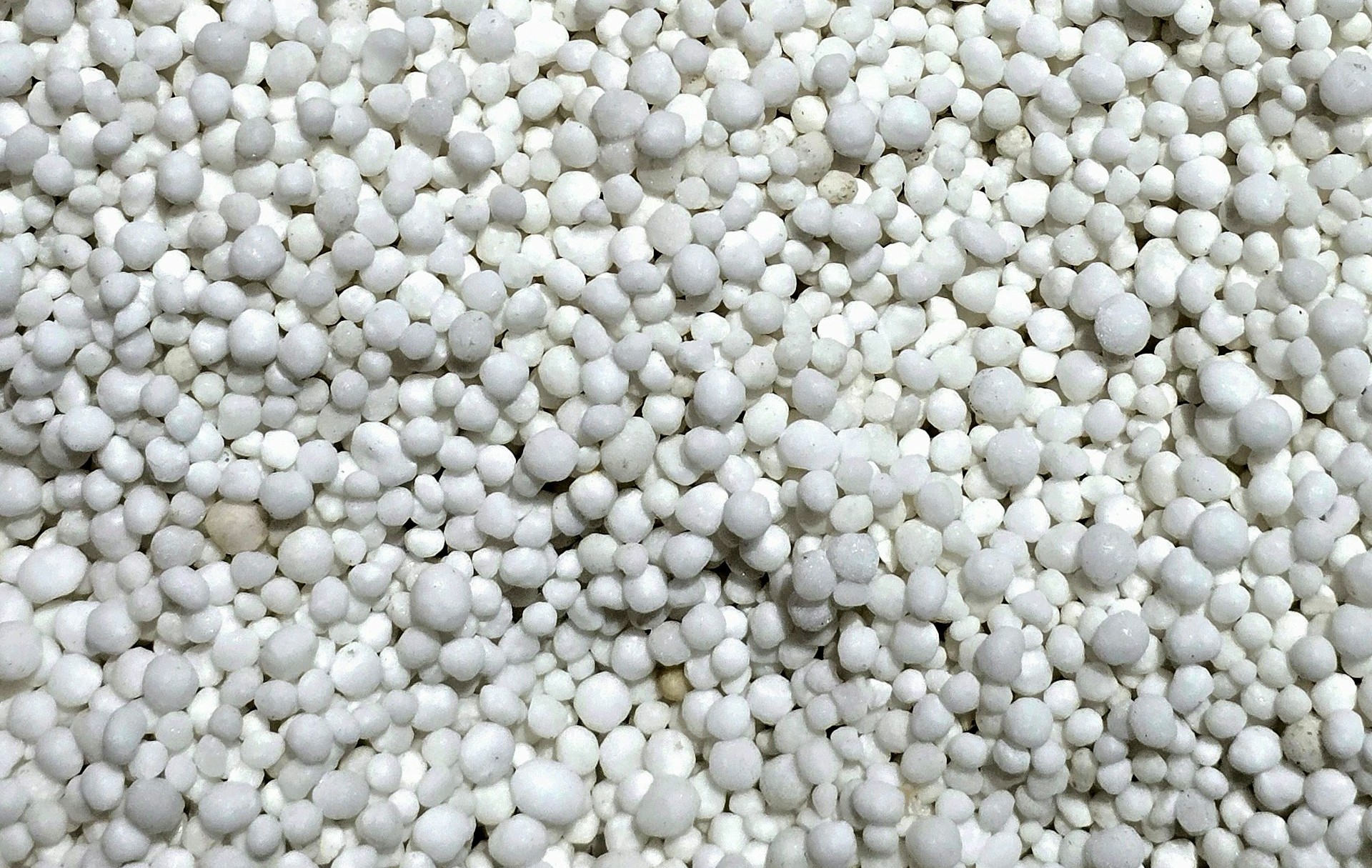

Morocco’s wheat import support mechanism is triggered when international prices surpass a set benchmark of around $28 per quintal. With current market prices below that level, the subsidy remains unnecessary. Over recent months, the international price of soft wheat has remained low, especially across Morocco’s traditional European suppliers such as France, Germany, Poland, Lithuania, and Romania.

The ongoing harvest season in the Northern Hemisphere is expected to produce abundant volumes, which should keep prices competitive through the end of summer. This allows Morocco to secure strategic imports without resorting to public compensation.

Earlier in 2025, when international prices were slightly higher, Morocco’s support payments peaked at $1.52 per quintal in March and fell to $0.72 in April before being suspended entirely as prices declined.

Strategic extension through year-end

The Moroccan government has extended the broader wheat import management program—covering both import facilitation and incentives for strategic storage—until December 31, 2025. This ensures continuity in supply planning, even as subsidies remain dormant for now.

This approach aims to balance flexibility with fiscal prudence. Should global prices rise sharply, the government retains the ability to reactivate the subsidy mechanism swiftly to stabilize the domestic market.

Heavy dependence on imports amid drought

The subsidy freeze comes against the backdrop of a severe and prolonged drought that continues to hamper domestic cereal production. Morocco is currently experiencing its seventh consecutive year of drought, leading to one of the weakest harvests in recent memory.

During the 2023–2024 season, total national production of soft wheat, durum wheat, and barley fell to just 3.1 million metric tons, down 43% from 5.4 million tons harvested the previous year. This sharp decline has increased reliance on imports.

In 2024, Morocco imported 6.3 million metric tons of wheat, valued at approximately $1.84 billion. Despite the high volume, the overall import bill was 8% lower than the previous year due to falling international prices. The government has maintained incentives to encourage private sector stockpiling of cereals between April and December, reinforcing national food security.

Kazakhstan emerges as a new supplier

While Europe remains Morocco’s primary source of wheat, the country is also expanding its import base to include emerging suppliers like Kazakhstan. According to data from Kazakhstan’s Grain Union, Moroccan imports of Kazakh wheat reached 158,000 metric tons during the first five months of 2025. In May alone, Morocco received 47,500 metric tons from the Central Asian country.

Kazakhstan’s overall wheat exports are forecast to reach 7.7 million metric tons during the current agricultural year, with over 6 million tons shipped between September 2024 and May 2025—a 47% increase compared to the previous year.

This surge in exports has been supported by Kazakhstan’s transport subsidy program, which provides logistical support of $300 to $500 per ton. By late June, over 420 applications for export subsidies had been submitted by Kazakh grain companies.

Benefits and risks of Morocco’s approach

By suspending subsidies while maintaining import incentives, Morocco has created a stable and predictable environment for importers. Domestic consumers also benefit from the continued availability of affordable wheat, while public finances are shielded from the burden of compensatory payments during a time of low global prices.

However, there are structural risks associated with the current model. Continued reliance on imports makes Morocco vulnerable to external supply shocks or sudden price surges. Moreover, the policy does little to address the underlying weaknesses in domestic cereal production, which will require long-term investments in irrigation, climate-resilient agriculture, and farmer support systems.

The extension of the subsidy suspension reflects a pragmatic, cost-conscious approach in the short term. Yet Morocco’s long-term food security will depend on whether the government can reduce import dependency and revitalize the national cereal industry.

As harvests wrap up across Europe and Central Asia by September, Moroccan importers are expected to continue monitoring global trends closely—timing their purchases to coincide with the post-harvest period when prices are often at their lowest.